In his latest Coffee Break Briefing webinar, Frettens’ own Insolvency Guru Malcolm Niekirk looked at centrebinding and how it can be used to do something in a hurry before creditors approve your appointment.

This is the summary of that briefing.

If you'd like to watch the webinar back, you can do so below, if not, read on for our summary...

The word centrebinding is derived from an old, now largely obsolete case, and has several different meanings. It describes:

- A particular process in creditors voluntary liquidations

- Sometimes an abuse of the liquidation process

- Sometimes a useful insolvency tool. And by that, I mean a way of using a CVL as almost a short lightweight administration.

This article focuses on the last bullet point.

Quick Links

- CVL appointments - the normal sequence of events

- What’s different in a centrebind

- The original centrebind case

- When to think about centrebinding.

- Court applications to extend your powers in a centrebind

CVL appointments - the normal sequence of events

The normal practice in a CVL is:

- The members pass the winding up resolution on the same day that the creditors appoint the liquidator,

- Members of the company vote, at an EGM, to put the company into liquidation, and appoint a liquidator,

- Either by deemed consent, or at a virtual meeting.

- Virtual meetings normally happen immediately after the EGM.

When the deemed consent procedure is used, the decision is treated as made at 11:59pm. In those cases, there may be a gap of a few hours between the members resolving to put the company into liquidation, and the appointment of the liquidators by the creditors being deemed to have been made.

For all practical purposes, the usual procedure means the company goes into liquidation, and the liquidator is appointed, all on the same day. It is unusual for there to have to be any further analysis of what happened when.

In those, usual, cases, there are a couple of key dates before the company goes into liquidation. They are:

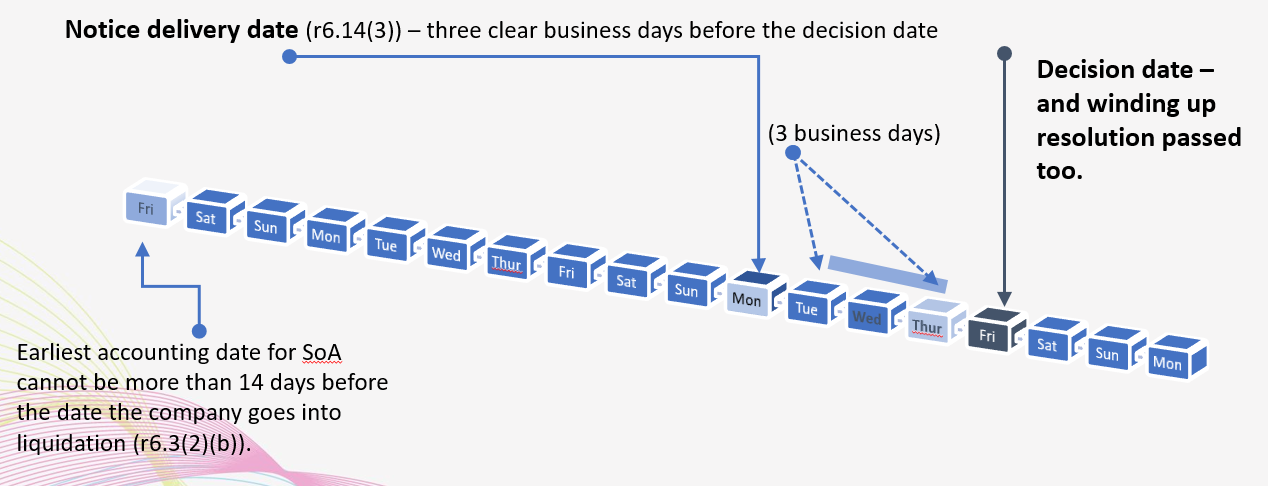

- The statement of affairs. The date to which this is drawn up must not be more than 14 days before the company goes into liquidation.

- Notices (under r6.14, of the virtual meeting or deemed consent), must be delivered to creditors at least three clear business days before the decision date.

What’s different in a centrebind?

In a centrebind, the members hold their EGM, and resolve for the company to go into liquidation, before the creditors’ decision date.

Because the company goes into liquidation when the members pass their resolution, the company will be in liquidation for a few days, before the creditors get to decide who is to be the liquidator. The EGM can be up to 14 days before the creditors’ decision date.

Normal practice would be for the members to appoint a liquidator at the same EGM as they decide to put the company into liquidation. The liquidator appointed by the members is therefore the liquidator (until the decision date, at least) even though no creditors have then voted for them.

As the date of the EGM is the date on which the company goes into liquidation, the earliest date for the statement of affairs is up to 14 days before the date of the EGM.

What about in a centrebind?

In a centrebind, the liquidator will take the company’s assets into their control pending the creditors’ decision date. But, the liquidator’s powers are very limited. That is to prevent centrebind abuse.

If the creditors’ decision is delayed, the duration of the centrebind will be extended.

How are the liquidator’s powers limited during a centrebind?

Suppose a liquidator has been appointed by the members, but with a gap, pending the creditors’ decision. In that case, until the creditors have affirmed the liquidators’ appointment (or appointed another), the liquidator’s powers are very limited.

In that time, the liquidator needs authority from the court to exercise their general powers. They do have emergency powers that they can use, at their own discretion, and without a court order. Those emergency powers allow them to take control of the company’s assets, sell perishable goods, and protect the company’s assets.

The original Centrebind case

The order of events

28 September 1966 - Inland Revenue distrained (seizing the company’s goods for unpaid taxes).

2 November 1966 – Notices of the meeting of creditors were sent to the creditors.

8 November 1966 – The company’s members held an EGM short notice, choosing to wind up the company and put it into liquidation and appoint Bernard Philips as the liquidator.

9 November 1966 – The liquidator applied to the court to stay the distraint.

15 November 1966 – The hearing in the High Court. This was the question: Was the liquidator’s appointment valid?

18 November 1966 – The date set for the meeting of creditors.

The law in 1966

Although the procedure for putting a company into a CVL was similar, in 1966, and used similar terminology, there were significant differences.

In particular, the company had to hold the EGM to wind up the company on the same day as the meeting of creditors (or the day before). Also, the company had to send notices to creditors at the same time as to members.

Clearly the company had not complied with this. It held an EGM, on short notice, several days before the meeting of creditors; but after notices had gone out to creditors.

At that time, the statutory rules for putting a company into CVL were in the Companies Act 1948 (now, of course, repealed). The only consequence, in that Act, of breaking this rule was that the directors, or the company, could be fined.

The Inland Revenue argued that this breach of the law should render the decisions of the EGM invalid. If they were right, the company would not be in liquidation, and Bernard Philips would not be its liquidator. Thus he would have no standing to ask the court to stay their distraint.

The court disagreed, ruling that the EGM was valid and that the members’ resolution had put the company into liquidation and appointed Bernard Philips as liquidator.

So, the liquidator’s actions were valid and, therefore, the liquidator did have standing to ask the court to restrain the distraint.

Inland Revenue agreed to hold off from taking any further action on their distraint, so the court would have time to decide whether the distraint should continue.

This was a victory for the liquidator.

Consequences of the case.

The Centrebind decision had these consequences:

- Centrebinding became an established procedure; a practical way of protecting the assets of an insolvent company.

- Centrebinding became an abuse. At that time, there were no regulated insolvency practitioners. Some disreputable directors used the centrebinding procedure to appoint a cavalier liquidator, who might never call a meeting of creditors.

- When there was a major reform of insolvency legislation, leading to the Insolvency Act 1986, liquidators’ powers were cut to the absolute minimum in a centrebind.

- Also as part of those reforms, the insolvency profession became properly regulated and licenced.

When to think about centrebinding

In these cases centrebinding might be a sensible decision:

- When perishable or depreciating assets need to be sold.

- When the company’s assets need to be protected, to ensure stock remains in safe custody.

- To protect assets from being taken to enforce a judgement debt.

Protecting assets from a landlord

Centrebinding can also be used to protect the company’s assets from a landlord. The courts will normally stop a landlord from distraining on the company’s goods, in cases where the landlord did not start the distraint before the company went into liquidation.

A centrebind can therefore stop the landlord from starting commercial rent arrears recovery (the modern day replacement for distraint). Also, the courts stay legal proceedings once a liquidator is appointed in a centrebind, to stop a landlord from forfeiting a lease.

Trading the business

A liquidator appointed by the creditors has the power to trade the business, though it is not one of the emergency powers that a liquidator has in a centrebind. However, in a centrebind, the liquidator can ask the court to grant this power (and others) to the liquidator.

In a centrebind liquidation (as any other) suppliers’ rights to terminate contracts are restricted by s223 and s233B Insolvency Act 1986 (which limit their powers to use ipso facto clauses).

Court applications to extend the liquidators’ powers in a centrebind.

These are additional powers that a liquidator might ask the court to confer in a centrebind:

- The power to stop creditors from bringing proceedings against the company (or enforcing judgments).

- The power to trade the business.

- Staying legal proceedings that have been threatened, but not started.

- Staying enforcement that has been threatened by various types of creditor, such as judgement creditors, landlords, Retention of Title creditors and suppliers.

Upcoming events

Thanks for reading this summary…

My next Coffee Break Briefing will be in the new year on 8th January 2023, where I’ll be talking about ‘Avanti Communications – is it a fixed, or floating charge?’. Sign up for free here.

Our Third Annual all-day in-person Insolvency Conference will be taking place in 2024. Date and venue to be confirmed.

Make sure you’re subscribed to our email list to receive event information and webinar links straight to your inbox.

Specialist Insolvency Solicitors

If you have any questions after reading this article, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with our bright and experienced team.

Call us on 01202 499255, or fill out the form at the top of this page, for a free initial chat.

Comments